Marcel Duchamp and the Fountain Scandal / April 1-December 3, 2017

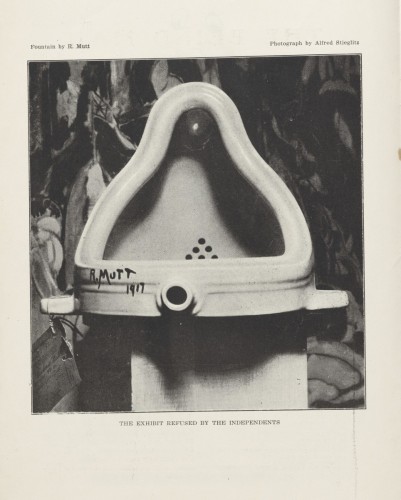

“Marcel Duchamp and the Fountain Scandal” Fountain by R. Mutt, 1917, Alfred Stieglitz, Published in The Blindman

To celebrate the centennial of one of the greatest—and most amusing—controversies in the history of modern art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art is presenting an exhibition on Marcel Duchamp’s legendary “readymade,” Fountain. Marcel Duchamp and the Fountain Scandal focuses on the spring of 1917, when Duchamp, with the help of several friends, notoriously submitted a porcelain urinal to an unjuried exhibition held by the Society of Independent Artists in New York. Purchased from a store that sold plumbing fixtures, this object, which was titled Fountain and signed “R. Mutt” was rejected by a vote of the organizers, touching off a fierce debate. The Museum’s exhibition explores Duchamp’s staging of this controversy and highlights the radical ideas that were sparked by this crucial episode in the history of avant-garde art.

Timothy Rub, the George D. Widener Director and CEO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, said: “One hundred years ago, Duchamp’s Fountain turned the art world upside down. As artists and critics debated whether this was art or a hoax, the artist’s designation of the porcelain urinal as a readymade changed the course of modern art. Today, young artists continue to find inspiration and sources of provocation in it, and thus it is fitting that we return to this object and consider its continuing importance a century later.”

The exhibition is presented in Gallery 182, in which many of Duchamp’s celebrated masterpieces have been displayed since 1954. It details the story of Fountain and the roles of the colorful cast of characters around it, from the celebrated photographer Alfred Stieglitz and collector Walter Arensberg to the writer and artist Beatrice Wood. The exhibition includes period photographs, publications, and numerous other readymades, all from the Museum’s unrivaled collection. It takes an especially close look at the readymades, objects that the artist chose, signed, and sometimes inscribed with mysterious phrases. Duchamp considered them his greatest achievement.

The Society of Independents was founded in late 1916 by a group that included Duchamp. In meetings at the apartment of the collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg and elsewhere, the group planned a large exhibition for the following April. It decided that no jury would control artists’ participation in the show. Duchamp bought his urinal from the New York showroom of the J. L. Mott Iron Works. He signed and dated it “R. Mutt 1917,” and had it submitted to the exhibition. Upon its rejection, Duchamp resigned from the Independents in protest, as did Arensberg. A few days later, Duchamp brought Fountain to Stieglitz, who photographed it for The Blind Man, an avant-garde magazine published by Duchamp and his friends. In its May issue, the magazine defended the work, an editorial by Wood declaring: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.” The Museum’s exhibition includes a reproduction of the publication; visitors can turn the pages.

The original Fountain was soon lost or destroyed. In the Museum’s exhibition, it is documented by a printer’s proof of Stieglitz’s photograph that appeared in Blind Man, showing it displayed on a pedestal before a painting by Marsden Hartley at Stieglitz’s gallery, “291.” It is seen also in a photograph by Duchamp’s friend Henri-Pierre Roché, in which Fountain hangs above a doorjamb in the artist’s studio at 33 West 67th St. The Museum’s version of Fountain, the earliest of 14 full-size replicas, was signed and dated “R. Mutt 1917” by Duchamp in 1950.

Matthew Affron, the Muriel and Philip Berman Curator of Modern Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, said: “Duchamp understood quite early the profound challenge that the readymade posed to widely held ideas about the significance of originals and copies in art. As time went on, he became more interested in making replicas. He overturned ideas of originality, raising questions that have only grown in significance during our time, and so one hundred years after its conception, Duchamp’s readymade sculpture continues to bewilder.”

This exhibition is made possible by the Young Friends of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Curators

Matthew Affron, The Muriel and Philip Berman Curator of Modern Art

John Vick, Collections Project Manager

Duchamp at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Philadelphia Museum of Art contains the world’s most comprehensive collection of works by Duchamp, from his earliest paintings to his final work, along with the largest archive devoted to the artist. Among the original readymades are With Hidden Noise, 1916, and 50 cc of Paris Air, 1919. Replicas of readymades that were lost include Bicycle Wheel, 1913, and Bottlerack, 1914. Other highlights are Nude Descending the Staircase (No. 2), 1912, which had been a succés de scandale at the New York Armory Show in 1913, and two other versions of the painting. In addition, the Museum contains The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, which Duchamp himself installed in Gallery 182 in 1954, shortly after the Museum received the renowned collection of modern art given by Louise and Walter Arensberg. On view in an adjacent gallery is Étant donnés, completed in 1966, which entered the collection following the artist’s death in 1968. The artist Jasper Johns has called Etant donnés “the strangest work of art any museum has ever had in it.”

Social Media @philamuseum

https://press.philamuseum.org/marcel-duchamp-and-the-fountain-scandal/

Comentarios